Regrets, we've had a few

On the power of regret, novelists vs songwriters, iambic pentameter vs the four-beat bar, rhythms in prose and waves in the mind, and why only one of us has an inner monologue (guess which).

For anyone new here, Songwritings is a conversation between Kate van der Borgh (copywriter, D&AD Masterclass trainer, singer, musician) and Nick Asbury (copywriter, poet, Perpetual Disappointments Diarist, with a side interest in Tin Pan Alley songwriting).

NICK

So last time we had a great conversation with Jake about how I Wanted You To Know came together—and there was one thing I forgot to say. It wasn’t exactly in my head as I wrote it, but I’ve always thought of that lyric having a Remains of the Day feel about it—this idea of an unspoken love that never quite makes its way into words, all hidden beneath layers of English reserve.

Towards the end of that last post, we talked about the contrasts between novel writing (which you know a lot about) and lyric writing—and it’s interesting because Kazuo Ishiguro (author of The Remains of the Day) started out thinking of himself as a songwriter. He talks in this Guardian interview about how he aspired to being a musician, “but there came a point when I thought: actually, this isn’t me at all. I’m much less glamorous. I’m one of these people with corduroy jackets with elbow patches. It was a real comedown.”

Even in his elbow patch mode, he kept up the musical interest. In 2007, he worked with jazz singer Stacy Kent, writing lyrics for four tracks on her album Breakfast on the Morning Tram. It’s interesting that the lyrics (like this one for Ice Hotel) are actually pretty wordy, but maybe that’s a coincidence—I’m not familiar with everything he’s done. And I do like what he says in the Guardian interview about lyrics being partly about what you choose to leave out: “One of the key things I learnt writing lyrics—and this had an enormous influence on my fiction—was that with an intimate, confiding, first-person song, the meaning must not be self-sufficient on the page. It has to be oblique, sometimes you have to read between the lines.”

It makes me think more broadly about the relationship between songs and novels, and writers who have traversed both worlds. Any thoughts?

KATE

Thanks a bunch for posting that scene from The Remains of the Day. Harrowing. In one read, that book broke my heart several times over.

Ishiguro is a great starting point for a conversation about songs and novels. In this interview he says that, ideally, both should haunt people in some way: “Songs that really work, we carry them with us all our lives. And when things happen to us, or when we feel certain things, or perhaps just when we happen to be in certain places in the world, these songs come back as our soundtrack.” He asks of books: “Does it linger in that person’s mind?… Has it found a tiny corner in that person’s life?”

Having wondered what it is that makes certain works ‘haunting’, Ishiguro suggests: “Maybe having something unresolved—deliberately unresolved—in the work, is quite an important aspect of this.” What do you think? In both The Remains of the Day and I Wanted You To Know, there is a sense of resolution—arguably, the gut punch is that finality, the door finally closing. But of course the thing about regret is that even when we know a chapter in our life is finished, we go back over it, again and again, as if we could change the ending (exactly the feeling your lyrics describe: “I wander through a maze / Of turnings that I missed”).

All this reminds me of a book I read recently: The Pallbearers’ Club by Paul Tremblay. Don’t be put off by the horror label! While it’s definitely spooky, it’s also a very beautiful and sad faux-memoir that details the narrator’s difficult adolescence—and, in particular, his troubling friendship with a woman named Mercy. Was she an emotional vampire who brought out the worst in him? Or was she something more sinister? Music is a huge presence throughout, especially the music of the punk band Hüsker Dü.

And it makes sense that, in a book about looking back on youth, the narrator talks so much about the music he fell in love with as a teenager. That music often keeps such a powerful hold on us—to Ishiguro’s point, it takes us back to that painfully intense time of high emotion and sprawling futures. Feel like there’s something to say here about songs, stories, memories, regrets—all constantly returning, all ghosts.

NICK

Jeez, you already said a lot there! I definitely think there’s a phenomenon where the music you listen to aged 17–25 sinks in deeper and ‘haunts’ you for the rest of your life. It’s almost like a physiological / neurological thing where your brain is still growing and the music gets woven into it. And I think that naturally gets tied in with the bittersweet emotion of regret—because it’s not just a negative emotion, it’s a close relation of nostalgia and hopefulness. I believe our mutual friend Tom Sharp said ‘Grief is love moving backwards’—you could say regret is hope moving backwards.

To carbon date my own brain, one of my favourite songs from my aged 17–25 era was Regret by New Order: “Just wait till tomorrow / I guess that's what they all say / Just before they fall apart”. Sigh.

I will have to look up The Pallbearer’s Club, but I like what you say about music being a presence throughout the book—it makes me think of the wider relationship between novelists and music.

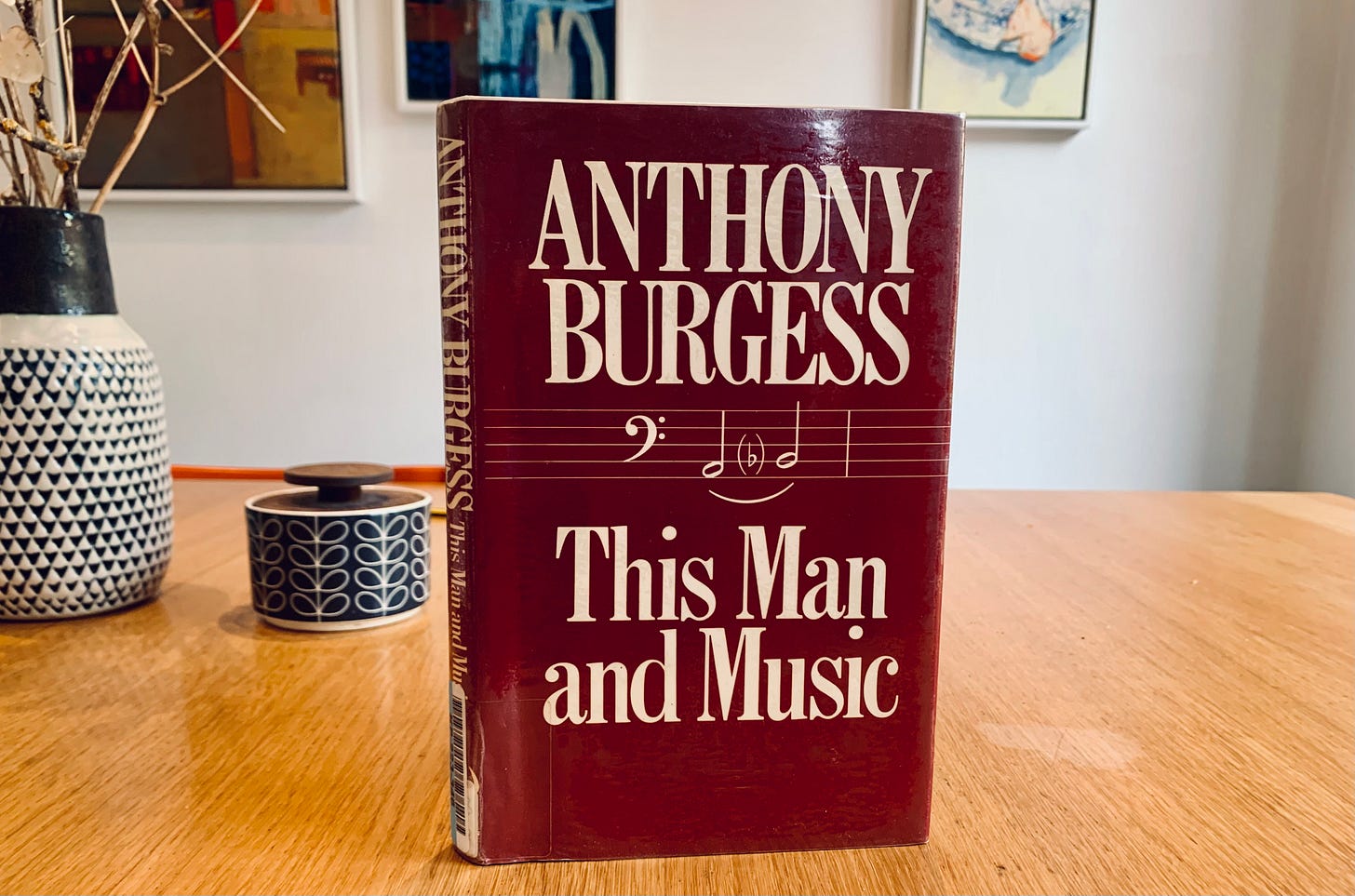

I was reading this recently, by Anthony Burgess (A Clockwork Orange). It’s mainly about his passion for classical music—he was a self-taught composer of several symphonies and once said “I wish people would think of me as a musician who writes novels, instead of a novelist who writes music on the side”. He also wrote Napoleon Symphony, which he describes as a novel in four movements.

But the chapter that really interests me is about the lyricists of Tin Pan Alley—he talks about how lyricists like Lorenz Hart “oscillate between the cynical and the sentimental”, aiming for “a very natural conversational declaration which, by the happiest of accidents, has rhymes in it”. And he notes how a lot of those lyricists existed in service of the performer: “We are not dealing with egotistical romantic poets, but with skilled craftsmen serving stars.”

He also makes a point that has haunted me since reading it: why is it that the four-beat bar is so natural to music, but English verse has taken the five-beat line as its go-to form? He blames a French and Italian influence which projected iambic pentameter onto a language that doesn’t naturally suit it: “Whether we like it or not, when we hear a five-beat line, we are really hearing a four-beat one followed by the first beat of a second which is not permitted to complete itself.” I haven’t got my head round all of it, but I recommend the chapter—it’s called Under The Bam.

KATE

Ha, it’s funny you say that, because I can clearly recall the English lesson where we first learned about iambic pentameter. I sat there, thinking: five beats??

Thinking about how rhythm works across music and prose… Lots of writers will know the quote from Gary Provost, which suggests that it’s a certain variability—unpredictability?—that gives prose an appealing rhythm. (That and all the other stuff about the stresses falling in the right places, I presume?!) However, in music it’s often a certain regularity of beat that keeps our toes tapping. Do you have any thoughts about that? I feel like I need to understand more about poetry here, the difference between regular metre and something more free.. When all writing has rhythm, what’s the boundary between poetry and prose?

In one of her letters, Virginia Woolf said: “Style is a very simple matter: it is all rhythm… Now this is very profound, what rhythm is, and goes far deeper than words. A sight, an emotion, creates this wave in the mind, long before it makes words to fit it; and in writing (such is my present belief) one has to recapture this, and set this working (which has nothing apparently to do with words) and then, as it breaks and tumbles in the mind, it makes words to fit it.”

Does this resonate with you, this ‘wave in the mind’? To be honest, I’m still trying to work out what it means to me. And, if you do experience waves—to perhaps go off on something of a tangent here—do you have an inner monologue? Or are you one of those people who ‘thinks’ in colours, sounds? I’m thinking about our different approaches to songwriting, and I’m wondering whether my (admittedly limiting) tendency to have the words lead the music is anything to do with my absolutely deafening inner monologue…

NICK

OK, we may have hit bedrock here! I have NO inner monologue! At least, I don’t think I do—and it sounds like I’d know about it if I had.

I’m fascinated to know more about yours—does it tell you what to say next when you’re writing something? Does it say “And so Kate puts the kettle on” when you’re making a cup of tea? Or is it more like the inner critic saying “Who do you think you are?” Either way, have you always been aware of it?

For my part, I wouldn’t say I especially think in colours or sounds either—but that whole area of rhythm and waves is interesting, because I think that’s pretty deeply ingrained in me. Weirdly, I might think in rhythm more when I’m writing prose. So if I’m writing one of my long spiels about purpose, I’ll automatically think about the rhythm of the sentence, paragraph and overall argument (as in the Gary Provost quote you mention)—because rhythm is part of the rhetorical effect. And it’s a deep part, in the sense that I don’t think of it as just superficial decoration to make a bad argument sound better. It’s more that the sign of a good argument is that it will fall out in satisfyingly shaped prose. At least, that’s what I like to think. (Closely related to rhythm is the idea of pattern and symmetry—I like the Greek idea of arguments consisting of thesis, antithesis and synthesis—synthesis being the ‘third way’ that resolves the tension and moves the argument onto the next phase. Interesting that synthesiser is a musical term too.)

Conversely, when I write poetry, I feel a contrarian urge to go against the rhythm and break things up a bit. But then the poet I most admire technically is Philip Larkin, who had a brilliant sense of rhythm that was no doubt linked to his love of jazz.

KATE

It blows my mind when someone says they don’t have an inner monologue. What’s going on in there?!

It’s hard to describe my own—if I focus on it, it quietens (I read somewhere that understanding our inner monologues is like turning up the lights to see what darkness looks like). A lot of it is conversation: things I might say, things I should have said to other people. But I talk to myself too. At night I’ll say/hear: OK, you really have to go to sleep now.

Maybe the volume of my inner voice is connected to the fact that I don’t visualise things very clearly. A friend once posited that book lovers can picture characters and scenes vividly, as if there’s a movie in their head, but I don’t at all. Perhaps that’s why I try to write stories in a very visual way, pointing at certain sights in a certain order—because I have to, as much for myself as the reader. The cognitive scientist Stephen Pinker suggests that, in classic style, a writer presents a ‘window on the world’—‘he orients the reader’s gaze so that she can see it for herself’—and for years I’ve found that to be massively useful advice. The eternal human challenge: trying to get other people to understand what’s going on in our own heads!

Interesting what you say about thinking in rhythm. I’m not sure I do that, but I definitely think in big shapes—I’m conscious of an overarching flow, and of how a story will have to contract and relax over time. A very clever friend who works in TV once said that screenwriting is all about ‘architecture’, which I think is probably true for most writing (your point about the Greek structure leads us nicely onto three-act structures and other ‘templates’ that writers end up tussling with). But it’s easy for us to forget all that when we’re focused on the detail of turning the perfect sentence…

NICK

Speaking of which, Clive James turned a few perfect sentences, and he’s another writer who comes to mind in this whole context. He’s best known for his memoirs, essays, journalism and poetry. But like Anthony Burgess, he yearned to be known primarily as a songwriter, and came close to achieving it. A 1973 article by Charles Shaar Murray cited Clive James and his musical partner Pete Atkin as one of the best songwriting duos of their time (alongside Jagger and Richards).

They were heavily influenced by the Tin Pan Alley era, though Clive James’s lyrics tended to be wordier and more narrative in form. Personally, I struggle to warm to Pete Atkin’s singing style, but I do love the way Clive James writes and talks about music. He once told John Peel, “This is the work I’m known least for, but which is closest to my heart”. There’s a book called Loose Canon that’s worth seeking out.

KATE

One thing that struck me about the clip you shared is how Clive James talks about being inspired in his writing and music by a childhood painting set. He says: “That often happens to me now. When I’m writing, I go right back to my earliest vocabulary. Childhood vocabulary.”

It makes me think about your definition of regret: ‘hope moving backwards’. Such a lovely phrase. Gave me a little shiver, actually. Hope is so rich and complex, maybe even more so than love. (I think of the Pandora myth and of how, when all the evils of the world escape from the jar, hope is left behind… But is hope a comfort? Or another evil? And is it even hope?? Some say that ‘expectation’ is a more accurate translation…) I wonder if, in the end, that’s what our favourite music and our greatest regrets share—they take us back to a time of possibility.

And, to take us all the way back, maybe your Greek argument structure helps us to more fully understand the lack of resolution that Ishiguro is talking about. In The Remains of the Day, the narrator arguably goes through thesis and antithesis—he has an initial vision of the world that is challenged—but he never moves on to the synthesis part. Yes, he sees the truth of his life, momentarily. But he ultimately rejects it, because it’s too painful, and instead of growing and moving forward with new knowledge, he circles back to being the person he was at the beginning. Sob.

NICK

And so the bus of this Substack post pulls away and the reader is left weeping in the rain.

Or something like that.

On a more upbeat note, I feel like there are about 50 potential song ideas in this conversation. “Turning up the lights to see what the darkness looks like” is a great album title.

Thanks everyone for reading—would love to hear any of your thoughts, whether in comments or via email. We’ll return with another song and more writings soon. In the meantime, new readers can hear I Wanted You To Know and check out the accompanying conversation with Jake here.

Really enjoyed the dialogue here. Thanks! When you started exploring the inner monologue it made me think of internal family systems, a form of therapy developed by Dick Schwartz. You may enjoy exploring that if you e not before. I’ve found it to be a huge and productive paradigm shift for my inner world journeys. It has also reshaped how I go about songwriting and producing. Thanks again I’m glad I found you here!